Pakistan cricket great Wasim Akram reveals struggle with cocaine addiction in new book

In a new book, Wasim Akram reveals for the first time how he became an addict after his retirement from cricket – and how his wife’s death cured him.

The phone line from Australia to Karachi is not the greatest, but there is no mistaking the voice of possibly the most skilful left-arm fast bowler cricket has ever seen. Wasim Akram’s tone is seemingly always sunny, smiling almost, belying what has been a turbulent life on and off the field, and the message he is imparting.

He has written a new autobiography, Sultan: A Memoir, containing parts shocking in their frankness. “I’m a bit anxious about the book,” he says, “but I think once it is out, I’ll be kind of over it. I’m anxious because at my age, I’m 56 and I’ve been diabetic for 25 years, it is just stress, you know … it was tough to revisit all the things. I’ve done it for my two boys, who are 25 and 21, and my seven-year-old daughter, just to put my side of the story.”

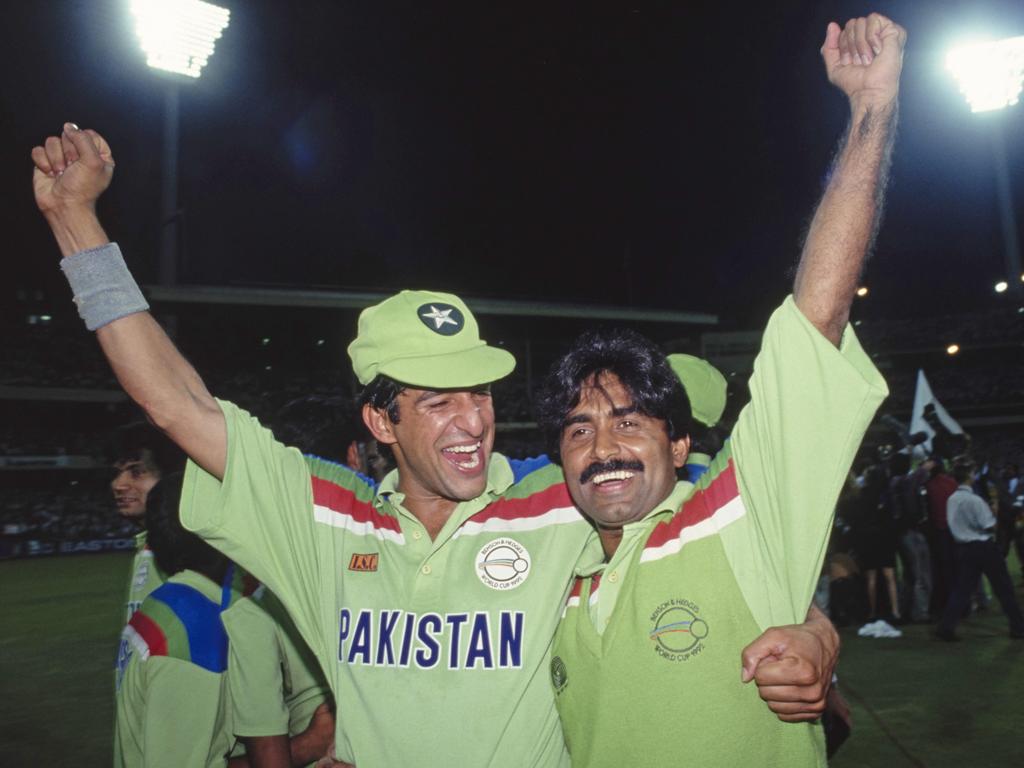

A man with more than 900 international wickets to his name and a World Cup winner from 1992, Wasim is still one of the biggest brands in Pakistan with sponsors and advertisers, but concedes: “I don’t know what happens after this book.”

He knows that many will be interested in what he has to say about allegations of ball-tampering and match-fixing, but those topics he found relatively easy to talk about. On those issues, he says, “I have nothing to hide.” It was addressing his addiction to cocaine in his post-playing days that was hard. With his late wife Huma at home in Manchester or Lahore with their young sons, he was travelling a lot, appearing on talk shows, doing commercials and reality TV.

“I liked to indulge myself; I liked to party,” he writes. “The culture of fame in South Asia is all consuming, seductive and corrupting. You can go to ten parties a night, and some do. And it took its toll on me. My devices turned into vices.

“Worst of all, I developed a dependence on cocaine. It started innocuously enough when I was offered a line at a party in England; my use grew steadily more serious, to the point that I felt I needed it to function.

“It made me volatile. It made me deceptive. Huma, I know, was often lonely in this time … she would talk of her desire to move to Karachi, to be nearer her parents and siblings. I was reluctant. Why? Partly because I liked going to Karachi on my own, pretending it was work when it was actually about partying, often for days at a time.

“Huma eventually found me out, discovering a packet of cocaine in my wallet … ‘You need help.’ I agreed. It was getting out of hand. I couldn’t control it. One line would become two, two would become four; four would become a gram, a gram would become two. I could not sleep. I could not eat. I grew inattentive to my diabetes, which caused me headaches and mood swings. Like a lot of addicts, part of me welcomed discovery: the secrecy had been exhausting.”

Wasim agreed to go into rehab in Lahore, but the experience proved traumatic. “Movies conjure up an image of rehab as a caring, nurturing environment. This facility was brutal: a bare building with five cells, a meeting room and a kitchen. The doctor was a complete conman, who worked primarily on manipulating families rather than treating patients, on separating relatives from money rather than users from drugs.

“The treatment was essentially sedation, with fistfuls of tablets to take in the morning and evening, coupled with lectures and prayer. I felt lethargic. I gained weight. For an hour a day I wandered round our little exercise yard like a zombie … I screamed at my wife. ‘I’ve got to get out of here.’ ”

He stuck it out for another seven weeks. He reflects now: “It was horrible. That scarred me for a bit … when people keep you against your will that pisses you off.”

The worst thing was it didn’t work. He lapsed into old habits. “Try as I might, part of me was still smouldering inside about the indignity of what I’d been put through. My pride was hurt, and the lure of my lifestyle remained. I briefly contemplated divorce. I settled for heading to the 2009 ICC Champions Trophy where, out from under Huma’s daily scrutiny, I started using again.”

Huma’s tragic death shortly after this from a rare fungal infection called mucormycosis, which doctors in Pakistan failed to recognise, changed everything.

“Huma’s last selfless, unconscious act was curing me of my drug problem. That way of life was over, and I have never looked back.” He has since remarried, to Shaniera Thompson.

Wasim acknowledges that his admission will shock and disappoint. He can only attempt to explain what happened by linking it to his retirement – his dalliance with drugs was “a substitute for the adrenaline rush of competition, which I sorely missed, or to take advantage of the opportunity, which I had never had”.

As a player, Wasim’s rise was precipitous, a Test cricketer by the age of 18 and national captain at 26. When his mentor Imran Khan, who viewed him as “the blue-eyed boy”, left the sport after the 1992 World Cup win a team of youngsters were rudderless.

“That’s where the problem happened,” he says. “There was no one to discipline or guide us, not in a kind of army discipline way, but in a nice way.” When Wasim was made captain, without any previous experience of such a role, he regularly phoned Imran for advice, but there was only so much he could do.

Nor was there much help forthcoming from the Pakistan cricket board, possessed of few staff and little backbone. When nine players refused to play under Wasim, costing him his position, the board failed to punish the rebels, and ended up passing the job to the “negative, selfish” Saleem Malik, with infamously corrupting consequences.

Wasim played on in the ranks, but on a tour to New Zealand kept himself apart, taking wickets but barely celebrating. “I wanted to prove a point,” he says. “Perhaps that gave me more willpower and motivation, and actually helped me in the long run. But it kind of messed me up psychologically.”

He found respite in his seasons at Lancashire, which he describes as the best part of his cricketing life. “That was fun. That’s the way anyone should be playing any sport. Play, give 100 per cent and move on. But that wasn’t the case in Pakistan in the 1990s.”

When Justice Qayyum’s report into match-fixing in Pakistan appeared in the early 2000s, it recommended that Wasim should be censured and barred from the national captaincy. The case against him was ambiguous but Qayyum’s commission found “there has been some evidence to cast doubt on his integrity”. Wasim admits that until he came to write the book he had never bothered to read the report – “I knew I was innocent” – but having now done so he finds its conclusions baffling and contradictory.

“Everything was he said, she said, I heard from someone else, Wasim sent a message through someone else. I mean it doesn’t even sound right. I know there is this younger generation of Pakistanis on social media, whatever they have read without any proof … when they say, ‘He’s a match-fixer’, that hurts.

“It’s embarrassing because my kids have grown up and they ask questions.” At one point in the book, he says of Qayyum’s findings, “the damage was done, and nothing could repair my reputation”.

Wasim is now working on a regular T20 World Cup show on Pakistan’s first HD sports channel, A Sports, and will be involved in commentary on England’s forthcoming Test tour, which he describes as “huge”.

“This country has been starved of cricket. It’s really the only sport we have here. It goes beyond a passion in this country, every youngster wants to be a cricketer.

“The tour will do a great good to cricket and to the country. Things here have improved a lot [since England’s last Test tour in 2005] – the food, the infrastructure, the security.

“It’s a huge deal that England are coming and it means that every other team will follow, fingers crossed.”