‘Shankly knew it was suspicious’: The day Liverpool was robbed in notoriously corrupt era

Liverpool’s 1965 loss to Inter Milan still leaves those involved seething with the referee. It was a notorious example of the Italian corruption of that era, writes PAUL JOYCE.

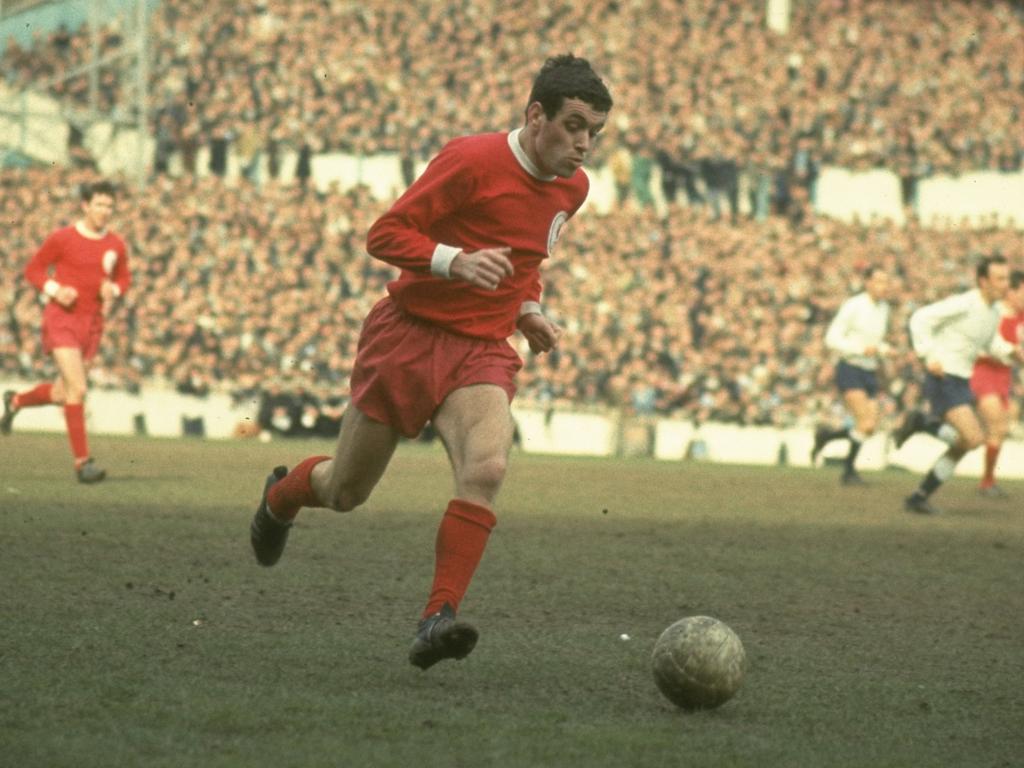

Even now, almost 60 years on, it is easy to detect the frustration in Ian Callaghan’s voice. So much so that he repeats one phrase for effect.

“You just got the impression that it wasn’t a game we were going to win,” he says. “It wasn’t a game we were going to win.”

Liverpool’s trip to Inter Milan on Wednesday signals the continued pursuit of success but, for an older generation, the assignment also stirs memories of a bygone era and an outcome which still rankles.

Bill Shankly’s side headed to the San Siro in May 1965 cherishing a 3-1 victory from the first leg of the semi-final, at Anfield, and within sight of progress into the European Cup final in what was their first continental campaign.

They would lose 3-0 on a controversial, chastening evening when they cursed less the names of Inter’s scorers but that of the Spanish referee José María Ortiz de Mendíbil, a man whom Shankly would later say haunted him to his dying day.

From the moment Liverpool arrived in Italy an uncomfortable experience ensued. There were suggestions in the Italian media that the visitors were drug cheats, while other elements of the trip proved far from straightforward.

Liverpool stayed in a hotel next to a church where the bells rang each and every hour. Shankly and his assistant, Bob Paisley, arranged a meeting with the monsignor to try to negotiate a temporary halt. While sympathetic, the monsignor demurred with Shankly then going as far as suggesting Paisley should swathe the bells in bandages to try to dull the noise.

On the pitch, everything that could go wrong did. The first goal, from Mario Corso in the eighth minute, came when he curled an effort straight into the net from an indirect free kick. Joaquín Peiró scored 60 seconds later when he kicked the ball out of Tommy Lawrence’s hands.

Grainy footage of the incident shows Ortiz de Mendíbil waving away Liverpool’s frenzied and persistent protests. The die had been cast.

The great Giacinto Facchetti added a third for the hosts, who became world champions that same season, having beaten Argentina’s Independiente in a playoff game refereed by the same official. Ian St John had a goal disallowed in front of 76,000 supporters to complete Liverpool’s angst.

“There was a lot of controversy, the atmosphere in the ground was unbelievable and a bit sinister,” Callaghan says. “I don’t think we would have got out of the stadium if we had won.

“Tommy Lawrence had the ball kicked out of his hands and in Italy, in those days, you didn’t go near the goalkeeper. To have the ball kicked out of his hands and put in the net, it should never have been allowed.

“Shanks was just convinced we were never going to win. That, if you like, it was a fix. When you looked back at the things that happened in the game, it just seemed they all went for Inter. The things that happened in that game were suspicious.

“I remember when we went off the pitch, Tommy Smith had a right go. He even kicked the referee up the backside.”

While Peiro’s goal could be viewed as owing much to gamesmanship, it was Corso’s effort which added credence to Liverpool’s belief they had a genuine grievance.

A subsequent investigation by the Sunday Times journalists Brian Glanville and Keith Botsford, published in March 1975 under the headline “The Golden Years Of The Fix”, highlighted 11 matches they believed had been shaped by bribes. Inter-Liverpool was one.

The contrast with the first leg was stark.

Liverpool had won the FA Cup for the first time in their history three days earlier, beating Leeds United 2-1. The trophy would be paraded around the ground before kick-off by Gerry Byrne, who broke his collarbone early at Wembley but finished the game, and Gordon Milne, who had been injured the week before.

Yet, initially, when the victorious team pulled in at Anfield for the visit of the Italians, there was a sense of puzzlement.

“When we arrived the streets outside Anfield were deserted,” Callaghan recalls. “It was strange. Ron Yeats said, ‘No one has come to see us!’ But they were all inside. They had opened the gates early and the atmosphere inside the stadium was just something else. Electric.

“For me, that was one of the most exciting nights of my entire Liverpool career, playing Inter Milan.”

He scored too. Having dummied a free kick, Callaghan continued his run as Willie Stevenson found Roger Hunt who side-footed a cross for his team-mate to score.

“That is the most treasured goal of my career,” he says. “What made it even more rewarding was that we practised the free kick plan for some time and it was great to make it pay off like that.”

Callaghan, who turns 80 in April, could easily be viewed as Liverpool’s greatest player. In terms of longevity no one can match his 857 appearances, as he featured for the club in the old Second Division right through until winning the European Cup in 1977. He was on the bench the following year when Bruges were beaten at Wembley.

Certainly, he is most humble and unassuming. He works in the lounges at Anfield on match day and 20 minutes on the telephone serves as a rare treat as he opens up a window to a golden past. One which, along with his former team-mates Milne and Chris Lawler, he will be recounting during a stage show in May.

There is the story of how Shankly turned up at his house in Toxteth to convince Callaghan’s parents to let their son pursue a professional career in football rather than sign apprentice forms for a central heating company.

“As soon as he walked in, he had this charisma about him,” Callaghan, who took over from boyhood idol, Billy Liddell, in the side, says. “He gave me my debut in 1960 and in 1961-62 we came out of the Second Division. In ‘64, we won the league for the first time. It was just a marvellous, marvellous time.

“All this was going on when you had the music in the city too — the Beatles, Gerry and the Pacemakers. Liverpool was just alive. It was unbelievable, and being a local lad, it was a brilliant time.

“I enjoyed every minute of it. I was fortunate to play in the Seventies through to winning the European Cup but, for me, the Sixties era was absolutely fantastic. I wouldn’t swap it for football today. I know they are on fantastic money but, no, I enjoyed every minute.”

Callaghan’s thoughts will flit back through the decades on Wednesday, but he is enthralled by the team Jürgen Klopp has created. He hopes Carabao Cup success against Chelsea this month will add to the trophy haul of a squad determined to cement itself among Liverpool’s greats.

“They play attractive football, it’s a fantastic squad of players and an absolutely fantastic manager,” Callaghan adds. “He is not only a great manager, but a great personality. It is a special time for the club.

“He’s like Shanks in some ways. As soon as he arrived, the Liverpool fans took to him, which they did with Jürgen too.”

How The Sunday Times exposed the ‘golden years of the fix’

An investigation by Brian Glanville and Keith Botsford in The Sunday Times nearly 50 years ago exposed a plot to bribe referees in European competitions.

In April 1974, the paper accused Juventus of trying to bribe the Portuguese referee Francisco Marques Lobo to influence their semi-final second leg of the 1973 European Cup tie against Derby in the Italian club’s favour.

Lobo had been approached by Dezso Solti, a Hungarian match-fixer and an associate of the Juventus executive Italo Allodi, with an offer of $5,000 and a car. Lobo refused, reported the bribe and did not referee another international game.

Glanville and Botsford also investigated Inter Milan in the 1960s, where Allodi was club secretary and Solti his emissary. They found that the referee had been bribed in the 1964 and 1965 European Cup semi-finals against Dortmund and Liverpool.

In 1966 the Hungarian referee Gyorgy Vardas was approached but refused to influence the semi-final against Real Madrid. He also never refereed another international tie. Only Solti was ever punished — with a year’s ban.

– The Times