Brett Robinson and his mission to beat Rob de Castella’s fastest marathon record

Brett Robinson has one goal in life – to break a record and become Australia’s fastest marathon runner. But first he has to overcome the searing pain in his ribcage, writes ADAM PEACOCK.

For the first half of the marathons he runs, Brett Robinson is in a flow state, smoothly rolling through kilometre after kilometre in the most sadistic event on two legs.

Until it hits.

Around the 25km mark of the 42 to the finish line, Robinson gets a twitch in his rib cage.

“I start punching my stomach, digging my fingers in, changing my breathing,” Robinson says.

“It’s a spasm in my rib joints, but feels like I’m a kid at Little As getting stitch!”

It’s no stitch, and Robinson is no eight-year-old at the local track trying to punch out a few laps after a sausage roll and sunnyboy.

One minute he’s motoring along, then he has to slow to a jog. Tries to accelerate, it comes back. It’s been a heartbreaking mystery for five years.

Robinson runs with the elite pack. He was part of Eliud Kipchoge’s man on the moon moment for marathons, when the Kenyan smashed through the two-hour barrier.

Like Kipchoge, Robinson is chasing a time.

He wants one of the oldest records in Australia athletics history. The mind is dialled in for it. If only his body allows it.

*****

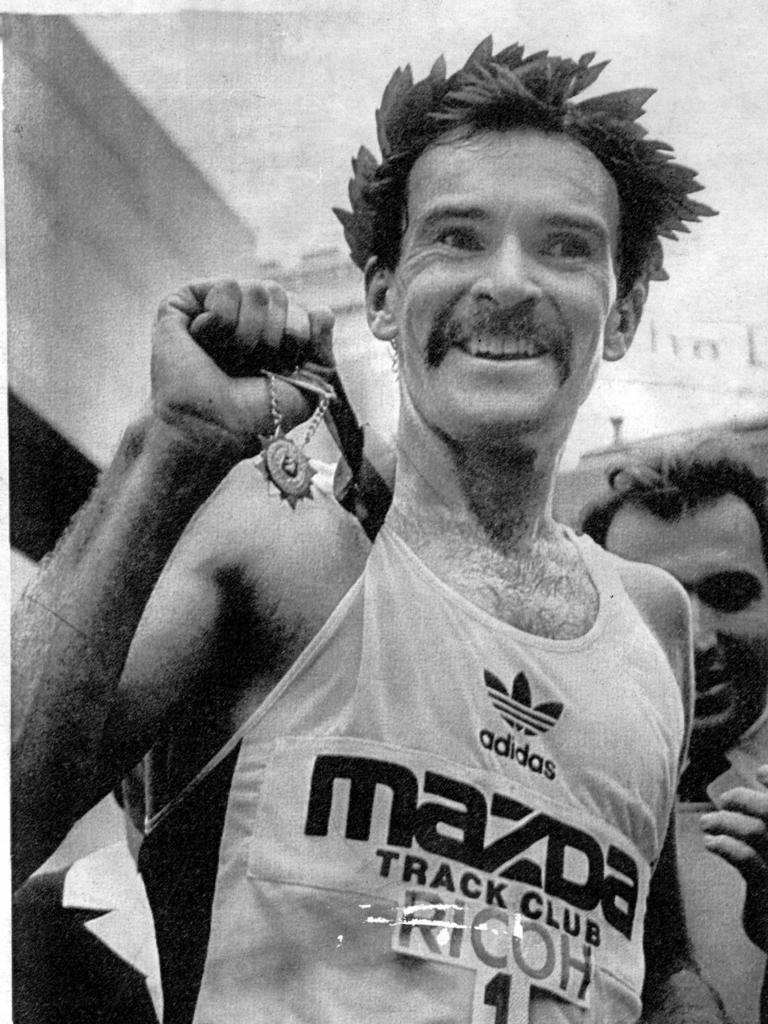

Thirty-five years ago, a familiar face with a familiar moustache sprinted across the finish line in Boston, skinny pale arms flailing in glory.

Rob de Castella – Deek! – Australia’s greatest marathon man, won the 1986 Boston Marathon in a time of 2 hours, 7 minutes and 51 seconds.

Broken down, it equates to running each kilometre in about three minutes. Forty-two times in a row.

Deek’s Boston win set an Australian record not bettered since. In terms of running events, only Peter Norman’s 200 metre effort at the 1968 Olympics – remembered for Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ Black Power podium salute – has stood for longer.

“I was just in great shape,” de Castella tells CodeSports about his Boston run.

“It was a good time, but with the advances of shoe technology I’m a bit surprised someone hasn’t been able to run that fast (since).

“Then again, I was pretty good!”

His punchline isn’t delivered with searing arrogance, but blunt realism. Marathons aren’t easy. He made them look that way.

“You’ve got to be proud of your achievements,” de Castella says.

“I trained so damn hard, and dedicated every breath and step to doing what I wanted to do. I am really proud of the results I got.”

Now 31, Robinson has built an impressive list of achievements in a similar way.

Robinson was a promising soccer player in Canberra with big lungs, and those big lungs pivoted to a life of running without a ball. Smart move. He started on the track, making a 5000m Olympic final in Rio, before pushing out to longer distances.

In 2020 he became the first Australian to break an hour for a half-marathon (21 kms), but the challenge of a marathon is his main focus now.

“I run once or twice every single day,” Robinson tells CodeSports from his Melbourne base, where the daily running can add up to 190 kilometres a week in training.

“You abuse your body for three months training for a marathon, then get to race day and abuse it even more. You know you’re going to hurt,” Robinson says.

In 2019, at just his second attempt at finishing a marathon, Robinson was on track to beat Deek’s record by two minutes in the London Marathon until, yep, the damn rib problem hit.

He pushed as hard as the burning sensation in his guts would allow, stopping the clock three minutes outside the record. A personal best, but the target remained.

Six months later in New York, he went all-in again.

“I led at the 32km mark, but then hit the wall,” Robinson recalls.

“The ‘wall’ is like waking up in the middle of the night and having to run. No energy. Pushing, nothing coming out. It’s not a nice feeling.”

Nothing compared to what was coming in his Olympic marathon debut.

Delayed by the pandemic, Robinson went to last year’s Olympics underdone in a racing sense due to lockdowns, but did all he could to prepare for the horrid heat and humidity in Tokyo.

“I ran in heat chambers, or went in the sauna for an hour after running to get ready,” Robinson says.

“Running a marathon in perfect conditions on the perfect day, it’s bloody tough. Then add 30 degree weather, 90 per cent humidity, it’s just brutal.”

Too brutal. The rib problem hit him at the halfway point again. He could only jog the last part, staggering home 15 minutes shy of his own personal best.

“Was an embarrassment really,” Robinson says.

“So disheartening. At the Olympics representing Australia and you’re jogging.”

Once the fog of disillusion cleared, Robinson knew he had to think laterally to solve having no control over his mid-race handbrake.

“I found a specialist in America,” Robinson says.

“They put sensors all over my body to see exactly how I run. It showed low mobility on my right side. My spine doesn’t twist there.

“And my right arm moves a lot, compared to my left arm, which is probably from running on a track around a bend the whole time.”

Specialists determined it all led to Robinson’s rib joints compressing at some stage past the halfway mark of a marathon.

He didn’t get it in training because marathon runners can’t train at or beyond full capacity. Robinson does 12 running sessions a week, and three of them are ‘max’ sessions, but even those are at about 85 per cent of race pace.

If he trained full pelt over a decent distance, the next day’s only certainties would be the sun rising in the east, and a trip to the physio.

Since the investigation in America showed imbalances, Robinson has added mobility exercises and rotational strength to his preparation.

“I feel more free now,” Robinson says.

“I’ve run two half-marathons since there hasn’t been an issue.

“But the real test will be in a marathon. Hopefully everything I’m doing is helping. We’ll see.”

****

Running is Robinson’s life.

The whole concept of one foot in front of another as quickly as possible fascinates him.

Aside from the 12 sessions a week, Robinson talks about running with good mate Joel Tobin-White in a podcast ‘For The Kudos’ and owns a business, Pulse Running, which helps recreational runners achieve their goals.

Whether it be waddling around the Tan in Melbourne, or going as quick as a Vespa for over 40kms, Robinson is acutely aware of one critical need – a flawless preparation.

He’s seen, and experienced perhaps the most famous example in his field.

In 2019 Robinson was invited by sponsors Nike to be a pace runner for Eliud Kipchoge’s mind-blowing two-hour marathon attempt in Vienna, which required the Kenyan to run every kilometre at the hedonistic pace of two minutes 50 seconds.

Pace-runners were assigned two five-kilometre blocks in which they had to be in perfect ‘flying’ formation around Kipchoge, to drag him along the Vienna-street circuit.

“There were 130,000 people on this 10km loop,” Robinson says.

“I was yelling at other runners but they couldn’t hear me. It was so loud.”

Everything went perfectly, and Kipchoge broke two hours.

The flawless preparation worked, to be remembered for the rest of time.

*****

Three years later, Robinson has planned for his own personal man on the moon moment, seeking Deek.

“It’s my number one goal, but it’s such a tough time,” Robinson says.

“I’ve tried going for the record before, and the wheels have come off.”

Robinson wants just one crack in 2022 at de Castella’s Australian record, in October’s London Marathon. Berlin is regarded as the quickest course in the world, and London isn’t far off, with the last 18 editions won in a quicker time than de Castella’s record.

Should Robinson stick with the lead pack, which he’s more than capable of, he’s a big chance but the prep needs to be nailed.

Which is why this weekend, Robinson is not in Oregon, USA for the World Championships, or Europe ahead of the Commonwealth Games.

Instead, he’s in Sydney, running the picturesque Sydney Harbour 10k event. Robinson aims to win, and 10,000 metres of quick steps equates to one step toward the record.

Racing on the road helps condition a runner to the brutality of harder tasks, and after Sydney, Robinson will head to the Sunshine Coast for a half-marathon in August, where he hopes to sit down with de Castella and discuss running faster than any Australian over 42.1kms.

“I’d love to see my record broken, and preferably not just by a few seconds, with all the shoe technology that’s around,” de Castella says.

“I’d really like whoever breaks my record, they really smash it, so I really know that they’ve done it as an athlete.”

Robinson is doing all he can to get the most out of himself.

The concern over his dastardly inhibitor, the rib problem, still lingers like a high cloud over an otherwise clear landscape.

Robinson won’t know for sure until past the halfway mark in London if those clouds will turn dark, or clear to allow him a fair shot at his own personal glory.

One way or another, it will hurt. There’s no other way in marathons.