Mac’s legacy: From the death of his son came Wayne Holdsworth’s mission to prevent youth suicide

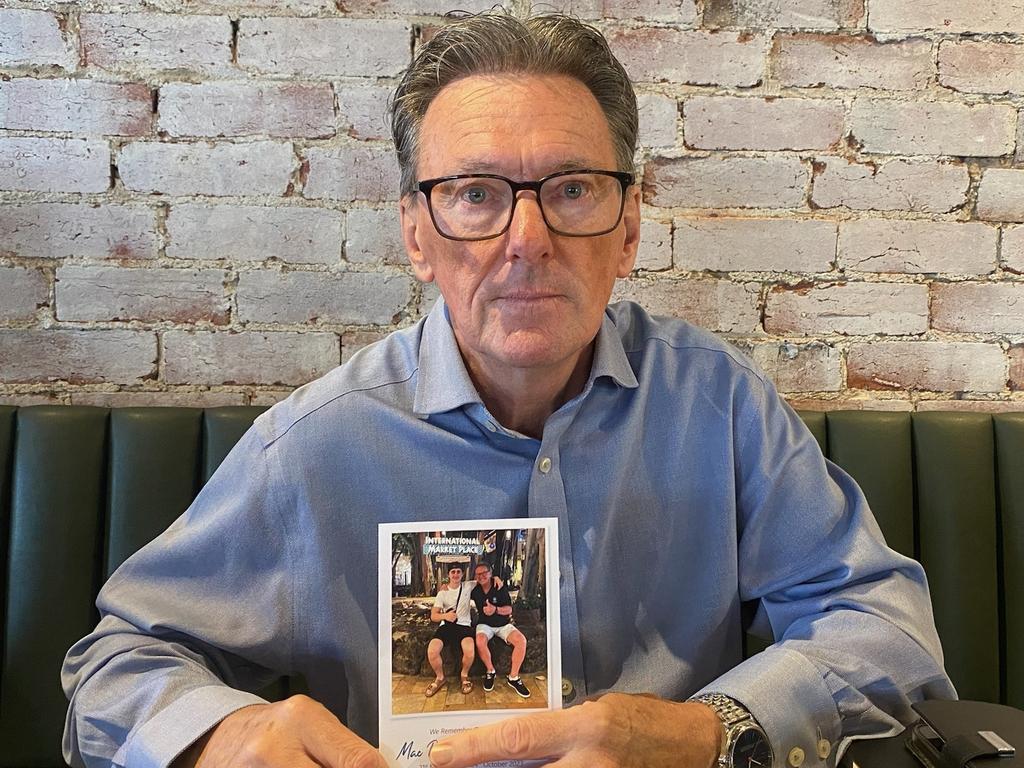

Mac Holdsworth took his own life at just 17. He was found by his father Wayne, who is on a mission for change to spare other families the same heartbreak, writes PAUL AMY.

Wayne Holdsworth does not want a question.

He wants a conversation.

Every day, he asked the question “Are you OK?’’ to his son Mac.

Every day, the teenager said he was OK.

“I’m fine, dad,’’ he would typically reply, quickly steering the talk to the latest football or cricket results.

Holdsworth accepted his word.

On October 24 last year, McKenzie Charlie Brennan “Mac’’ Holdsworth took his own life at the family home on the Mornington Peninsula.

He was 17.

Wayne Holdsworth, for many years a prominent Victorian sports administrator, found his son’s body.

On his computer, he had written a note apologising to his family and expressing what had troubled him.

Exactly 100 days before he took his own life, Mac’s natural mother, Renee, had died after a long period of illness that started with a diagnosis of MS.

Mac said he regretted not having spent more time with her before her death.

He had also been caught up in an online sexual extortion in which he sent an intimate photo of himself to a person he believed to be a young woman.

In fact, he had sent it to a pervert in NSW who blackmailed him and later distributed the photograph to Mac’s friends.

He tried to laugh it off but the episode humiliated him.

A 45-year-old man was last month jailed for five years over this and other extortion cases (Wayne Holdsworth went to the court hearing to read the victim impact statement Mac had prepared, outlining his embarrassment).

Mac also wrote in his note that he was suffering depression.

Wayne Holdsworth has been involved in Victorian sport, at all levels, for almost 40 years.

He was a staff member of the AFL when it was then the VFL, he was president of Ormond Amateur Football Club in the 2000s and he’s now chief executive of the Frankston District Basketball Association.

As part of his roles, he has helped deliver programs involving Head Space and Beyond Blue.

He was concerned about how his son was dealing with his mother’s death, which was why he asked him every day: “Are you OK?’’

He wishes now that he had taken it further, had pushed a little harder.

“In my view, it’s time not to simply ask the question, ‘Are you OK’,’’ Holdsworth says.

“It’s more about setting up a conversation, to inquire about the person’s actual feelings. Dig deeper. Say, ‘Are you happy?’ or, ‘Have you had any suicidal thoughts?’

“I know that’s confrontational but it’s important to save a life.

“Since Mac passed away, I’ve done so much research on what actually is working and what is not working. I view the ‘R U OK’ program as a tick-a-box program. It doesn’t delve deep enough into kids’ real feelings. One in five people here in Victoria have suicidal thoughts and we need to try to get to the bottom of why they have those thoughts so we can potentially save lives.

“If I’d asked Mac the question, ‘Are you happy? or, ‘Have you got suicidal thoughts?’ there would have been a gap, a pause, and that would have told me he did and I would have taken him to get help. I didn’t follow up. And that’s a regret that I have.’’

The night before Mac took his own life, the family had sat around the dinner table and enjoyed a meal of fish and vegetables prepared by Maggie, Wayne’s wife.

Mac’s sister, Daisy, was approaching her 15th birthday and he said he was going to take her out and buy her something.

The siblings also teased their father about his bad “dad jokes’’.

After father and son did the dishes, Mac went to his bedroom.

About 9pm, he poked his head out and told his father how much he was looking forward to driving to work the next day.

“I can’t wait to drive my car, dad,’’ he said. He was on his L plates and had done about 100 hours.

They were the last words Wayne Holdsworth heard his son say.

When Mac did not get up for work at 6.30am, his father went to his bedroom, entering after a knock at the door was unanswered.

He is thankful he found Mac; he does not like to think about what would have happened if young Daisy or Maggie had gone into the bedroom that morning.

“That (talk about the car) was another diversion, just like how he would bring up the footy and the cricket results in the car,’’ Wayne Holdsworth says.

“Our access to his internet history showed he’d planned it some months before.’’

He believes Mac was suffering a mental illness – “exactly the same as a physical illness but you just can’t see it’’.

“Compare it to cancer. With cancer, people know you’ve got it and can try to help you. With mental health, a lot of people do not share it and they then take the final act.

“If he’d known he was going to have 700 people at his funeral and had been able to see the outpouring of emotion and the love for him, he might have had second thoughts.’’

*****

Mac Holdsworth was a good footballer, captaining a junior premiership team at Moorooduc and his school side at Skye Primary. When he was in Grade 6, he was named school captain.

He was also an accomplished basketballer, with the Skye Sonics and then Frankston Blues, and followed the NBA avidly.

Being on the small side – Maggie called him “Mozz”, short for mosquito - he concentrated on football, going from Moorooduc to Seaford, and last year Mornington.

After leaving school at the end of Year 10, he landed an electrical apprenticeship but it was an unhappy time for him.

He later got a job at Mornington, building trusses, and he enjoyed it immensely; particularly the banter among the workers at smoko.

Every day he would rise early to ride to work, and when he got home he liked to tell his family about the one-liners he’d heard during the day.

“He was a hard worker and a really committed and dedicated boy,’’ Wayne Holdsworth says.

“He had the hardest and strongest handshake I saw in a young person. He was respectful, he was polite, he was cheeky, he challenged me.

“He was beautiful.’’

Holdsworth hosted Mac’s funeral service at Connect Christian Church in Frankston.

“I want a full house,’’ he said in a note announcing Mac’s death to the local basketball fraternity.

He got it.

Mac would have liked that. He was fixated with crowd numbers; a few weeks before his death, he was rolling numbers around in his head as he contemplated how many people would attend an AFL final at the MCG.

Holdsworth prepared the eulogy, going into details about his son’s life: where he was born, his schooling, his sport, his family life.

As he did, it struck him that Mac, for all his good qualities, had been too young to leave a legacy.

He is now trying to create one for him, working to prevent youth suicide.

“It’s part of my healing,’’ he says.

Counselling is too. All members of the family visit a counsellor once a week. They are doing their best to get by.

“It’s keeping us stable and it gives me the strength to do what I want to do, and that’s to use Mac’s death as a catalyst to help others,’’ Wayne Holdsworth says.

He has three main focuses.

With government and private funding, Holdsworth is planning to establish with Peninsula Healthcare a support service for young people.

It revolves around the concept of “listening’’ and involves the recruitment of about 30 volunteers.

Holdsworth says it will return the responsibility of community mental health “back to the community’’.

“At the moment, there’s a five-week waiting list at Headspace and that gives people an opportunity, from the time they’re sick, to potentially do something.

“What we’re setting up is something that’s 24-7.’’

He’s also pressing to have the Victorian Government spend more money and establish more resources for mental health.

Holdsworth points out that South Australia has suicide-prevention legislation that dictates a certain percentage of the its budget goes towards mental health.

He says NSW has the model on the agenda but Victoria does not.

Holdsworth is seeking a meeting with Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan to discuss the issue.

He is also campaigning to have suicide death numbers recorded and promoted in the media in the same way as the road toll.

He cannot understand why it isn’t being done already.

Holdsworth says there were about 800 suicide deaths last year in Victoria, compared to 299 deaths on the road.

“It should be publicised because it’s a significant issue in our society,’’ he says.

“Research conducted in 1974 indicated there were copy-cats out there and if a celebrity committed suicide and it was publicised, it could prompt others to do the same thing. With social media now, everyone knows how people die. All the reports in the newspapers carry the phone numbers for Beyond Blue and Lifeline anyway. We need to educate people, not ignore it.’’

*****

At his son’s funeral, Wayne Holdsworth noted in the eulogy that in his role at Frankston basketball, he used sport for “social and community benefit’’.

“It is the best role in the world,’’ he said.

“Last Tuesday week, we launched the disengaged youth program for kids that might go left and might go right. We’re hoping to inspire them to go right.

“We’ve also facilitated really big sessions for our community with Headspace because we know, particularly in this area, we’ve got some challenges. But I did not think I would be here today (reading) a eulogy for my boy.’’

Holdsworth says he’ll never get over the death of his son.

There will be within him a light that never goes out.

But he’s determined to create something lasting from a young life lost.

“His legacy is going to be in my work, trying to save lives,’’ Wayne Holdsworth says.