How triple F1 world champion Max Verstappen staked his claim as world’s most dominant athlete

Max Verstappen emerged from a hard-nosed upbringing with a hunger for racing that remains insatiable. JOSHUA ROBINSON got an inside look at what makes F1’s reigning triple world champion tick.

Max Verstappen sat in his navy Red Bull overalls, helmet on, hands on the steering wheel. He revved the engine twice, desperate to see what this machine could do. Then he floored the accelerator.

His tires screeched as he lurched forward at roughly the speed of a bicycle. Verstappen, 26, broke into a giggle. The fastest man in Formula One was sitting behind the wheel of a tiny Honda pickup truck with an engine barely more powerful than a go-kart.

Four days before the Japanese Grand Prix in September, in the middle of yet another endless sponsor obligation, this was how Verstappen was getting his kicks: driving the daylights out of 40 horsepower worth of lightweight Japanese engineering.

The remarkable part was that once Verstappen had explored the limits of this tiny truck, he proceeded to show the three other Formula One drivers in attendance how much better he was at driving this thing too. In every demonstration, the three-time world champion was quicker, sharper, and ready to prove that it doesn’t matter what kind of steering wheel is in his hands.

“I’ve been racing since I was four years old,” says Verstappen.

His preternatural gift for driving things fast has placed Verstappen in one of the most dominant phases of any driver in the 73-year history of the sport. He recently clinched his third consecutive drivers’ world championship and has won around two-thirds of all Grands Prix since 2021.

Formula One can’t entirely satisfy his urge to race. Verstappen spends much of his time away from the F1 circuit whiling away hours in competition against opponents who have never sprayed champagne from the top step of a podium, or been behind the wheel of a $10 million miracle of engineering. Some of them don’t even have drivers’ licenses. That’s because Max Verstappen’s other favourite place to go fast is in the world of computer sim racing, the e-sport version of motor racing. He’s among the best in the world there, too.

“He’s just driving and racing all the time,” says Red Bull team principal Christian Horner. “Which is fantastic. In any other form of sport … you can train. You can go and hit a golf ball or you can go and hit a tennis ball. But this, you can’t.”

Verstappen, who grew up in the Netherlands, hones his skills and satisfies his itch to win from the comfort of his own home in Monaco. That’s where he has spent hours recently learning the ins and outs of the new circuit in Las Vegas, where he will race for the first time this coming week — all while mopping the floor online with rivals he’s never met.

“It’s just that constant feeling of competition — trying to win there as well, trying to beat everyone,” he says. “I’m spending a lot of hours on it. But in a way, it’s also quite a quite relaxing thing to do.”

Verstappen’s ambitions for sim racing aren’t limited to trash talking teenagers on the other side of the world. In 2022, he launched Verstappen.com Racing to support his esports projects. He hopes to create a pathway for talented sim racers all the way to the real thing. It isn’t as straightforward as training airline pilots on simulators, but it isn’t quite as absurd as turning a Madden video game player into an NFL quarterback.

“I do feel that a lot of drivers have the potential to become a real driver,” Verstappen says. “Some of the sim racers are people who ran out of money sometimes and couldn’t afford to keep on going with go karting. Then you also have these people who never touched a go kart … and they never really get an opportunity to race a real car.”

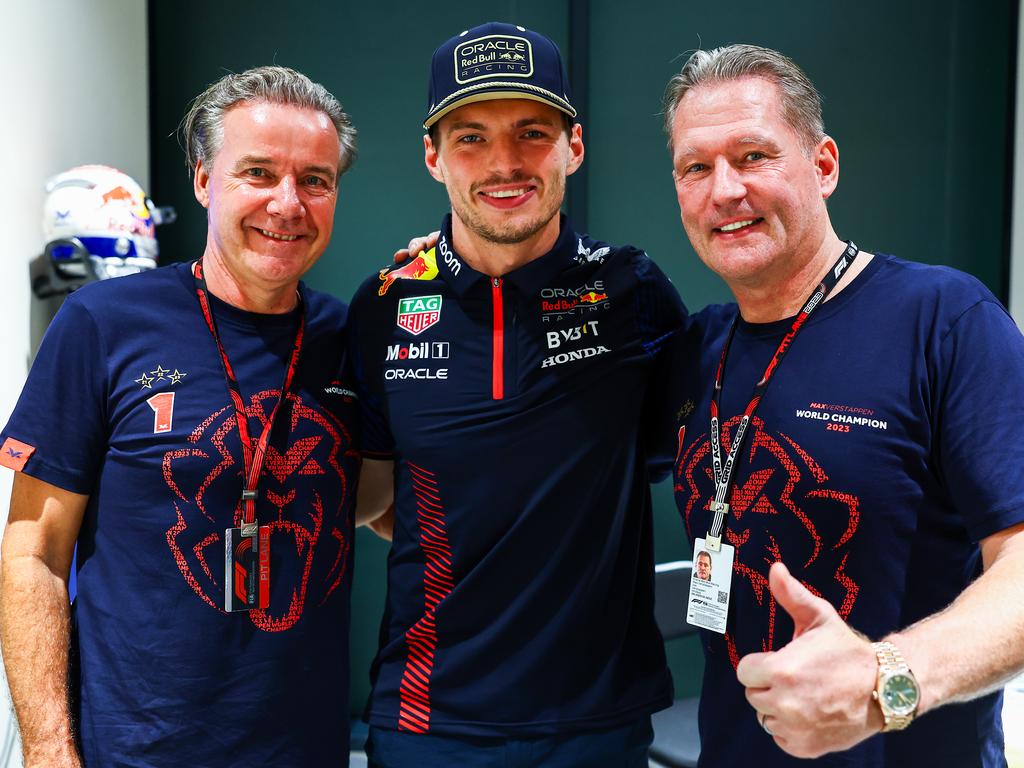

The idea is all the more striking when you consider that Verstappen was born into motor racing. His father Jos was a journeyman driver in F1 and became Max’s hard-nosed teacher. His mother, Sophie Kumpen, was a champion go-kart driver who once raced against a young British driver named Christian Horner.

Verstappen’s talent, combined with his lifetime of preparation, made him the youngest driver in F1 history on his debut as a 17-year-old in 2015. Eight years later, he has written himself into the list of all time greats. With a victory in Las Vegas, Verstappen would tie Sebastian Vettel for third on the career victories list, leaving him only behind seven-time world champion Lewis Hamilton and Michael Schumacher.

Verstappen won 17 of the 20 Grands Prix so far this season, breaking his own record for victories in a single season. He’s taken the checkered flag in 42 of the 64 races dating back to the start of 2021. The results have become so predictable that the 19 other drivers know they are mostly competing for second place.

“If he’s leading into Turn 2,” McLaren’s young British star Lando Norris says, “there’s not a lot you can do.”

*****

A couple of hours before the Japanese Grand Prix this September, Verstappen was hanging out quietly in his tiny room behind the pit lane. Many others use these final moments before the noise of the race to go through visualisation exercises or a physical warm up. Verstappen likes to nap. Failing that, he texts with friends or watches sim racing streams on his iPad.

This is what he always does. Anything else, he believes, would be counter-productive.

“Probably if I did that kind of preparation, it wouldn’t work for me,” Verstappen says. “I would get upset with myself, annoyed, having to go through all these kinds of procedures. But at the end of the day, if you get to the same result, it doesn’t matter what you do.”

The reality of the business today is that Verstappen ends up having to spend more time on photo shoots, promotional events, and all-purpose fan service than he does in the actual car. Over the course of the Grand Prix weekend in Suzuka, Japan, he spent only around four hours in the cockpit of his RB19. Verstappen had spent just as long fulfilling his duties to the Red Bull brand on the Wednesday alone. “I think from a young age, we grew up used to this kind of stuff,” he says.

After the tiny truck demonstration came a dizzying Honda meet-and-greet in a Tokyo nightclub (in the middle of the afternoon) where fans had paid up to $2,000 to sit on a couch next to him for 30 seconds at a time — autograph, photo, and onto the next one. Once that was over, Verstappen and three other drivers went through a Q&A and a short exhibition with sumo wrestlers.

“They eat 10,000 calories per day,” he was told on stage.

“I can do that,” said Verstappen, whose off-season cheeseburger habit is well known to Horner.

This more confident, more personable Verstappen is far cry from the kid who came into the sport with a reputation as a hothead. The reputation was somewhat deserved. The youngest guy out there drove with his elbows out, defended his territory at the very edge of legality, and lambasted his engineers over the radio. His perfect command of English was evident in his many ways of telling the team when he thought the car was worthless.

Verstappen happily ignored the niceties that F1 drivers learn as walking, driving corporate billboards. He was good at this game and he wanted everyone to treat him accordingly. Verstappen acted precisely like the teenager he was.

No one inside the Red Bull garage pretends that it wasn’t the case. But with experience, he overheated less often — although that’s not to say he isn’t prone to the occasional outburst. After finishing seventh last year in Singapore, he returned to his private room behind the garage, smashed up whatever he could with his helmet, and left without speaking to his team, according to a person who was there. That temper flares in sim racing, too, like the time Verstappen felt an opponent spoiled his lap, so he retaliated by ploughing his virtual car into the other guy’s virtual car.

His style of communication is more productive these days, especially when it comes to telling his engineers precisely how to improve the best car in F1.

“Unlike a lot of drivers, he doesn’t waste a lot of words on anything that doesn’t affect lap times,” says Red Bull’s technical director Pierre Waché. “He doesn’t have to try very hard to drive fast, so he has a lot of time to think.”

Verstappen uses that time to apply his uncanny attention to detail to the rest of the field. At 200 miles per hour, he somehow has the ability to keep an eye on the big screens set up around the circuit to see what the rest of the field is up to. According to his race engineer, Verstappen occasionally asks about Ferrari pit stops because over the radio he can hear the red cars having their tires changed in the next box over.

Verstappen can concern himself with what everyone else is doing because he has nothing left to prove. The serenity around his championship run this season couldn’t be more different from his first run to the title, back in 2021. That year, his battle with Hamilton went down to the final race of the season in Abu Dhabi, where Verstappen was only put in position to win through a late, controversial ruling by race officials.

Hamilton’s Mercedes team threatened a legal challenge. But once the dust settled, the result stood. After the most stressful season of his life, Verstappen was a world champion.

The two campaigns since, he says, have been significantly more pleasant. “I’ve definitely enjoyed this season more than the ’21 season,” he says.

That much is understandable. At times, it felt like he was the only one out there.

*****

Verstappen has heard all the complaints about his dominance. That his car is too good. That he’s made F1 boring. “It’s just a bit short sighted when you start to talk like that,” he says.

“When you look at all different kinds of sports, every one had this kind of domination and these are people who are always admired,” he adds. “You need that to happen to be able to talk about that 20 years later. Otherwise, everything is just average.”

Some in Formula One circles have wondered whether the sport should tweak its rules to level the field and give others a fighting chance against Red Bull. Over recent seasons, F1 has progressively introduced changes to make itself more competitive — the top teams, for instance, are granted less time for wind-tunnel testing and are subject to a strict cost cap — but critics argue that they haven’t done enough. Which is understandable if you happened to follow the sport in the 1990s and 2000s. Back then, the sport’s leadership wasn’t shy about regulating dynasties out of existence by outlawing any secret weapon they deemed to be too powerful.

F1’s chief executive, Stefano Domenicali, worked for Ferrari during its dynasty of the 2000s. But he has firmly ruled out making any rule changes to slow down Verstappen.

“If you have a good forward football player,” Domenicali says, “you cannot change the dimensions of the goal.”

The next meaningful shift in regulations, which would give rival teams their best shot at closing the gap to Red Bull, isn’t until 2026. By then, Verstappen, who is signed through 2028, has hinted he might be ready to think about something beyond F1. He says he’d like to try his hand at endurance events like the 24 Hours of Le Mans or the 24 Hours of Daytona — competition that is a little closer to traditional racing and a little less showbiz than F1.

More Coverage

Verstappen is also wary of the direction the sport is going in under its American owners, Liberty Media, who took over the series in 2017. Their tenure has seen F1 surge in popularity, due in part to the hit Netflix series Drive to Survive, and grow its schedule to a breaking point. Next year, the calendar features an unprecedented 24 races, including three in the U.S. Despite being one of the most successful Gen Z athletes in the world, Verstappen is distinctly old-school. He has little interest in fashion, music, or social media. Even the idea of racing in Vegas, as opposed to Italy or Belgium or Japan, doesn’t sit quite right with him.

“Of course, I understand why we go there. I personally, I’m a bigger fan of just the traditional tracks like here,” he said in Suzuka. “I think we have to really remember what the core of the sport is, and why people fall in love with the sport.”