Thorn in the NFL’s side for decades, the Davis family bring the Super Bowl to Las Vegas

Playing the Super Bowl in Las Vegas seemed an unlikely marriage. It’s even more unlikely, as JOSHUA ROBINSON and ANDREW BEATON write, given it was the legacy of the NFL’s arch rival in Al Davis.

Raiders owner Mark Davis had been pestering NFL commissioner Roger Goodell about the idea for years: He wanted the biggest sporting event in America to come to Las Vegas.

Though Mark has never been quite the source of chaos and disruption for the league that his father Al was, this was still a wild idea — even for the Davis family.

In those days, the city didn’t yet have its own team. Nor did it have a pro football stadium. But Davis, who would move the Raiders here in 2020, was determined to make this bonanza happen. He just needed Goodell and his fellow owners to agree with him. So the moment Davis gained relocation approval for his franchise in 2017, he went straight back to the NFL commissioner.

“When are we getting a Super Bowl?” Davis asked.

“Mark,” Goodell remembers answering, “let’s play a regular-season game here first.”

Nearly three dozen regular-season games later, Davis and the city he has helped transform into a global sports hub finally have their Super Bowl.

To the tens of thousands of fans who have flooded Sin City’s hotels, restaurants, and sports books, Vegas might seem like the most natural host city in the world. But making this happen took an unlikely partnership between the league and a family that have been at loggerheads for decades.

“I think it’s a marriage made in heaven,” Mark Davis said when Vegas was first selected to host the Super Bowl by the league and his fellow owners. “Some others may use a different word.”

The relationship between the Davis family and the NFL has come a long way. Before Al Davis owned a team in the league, it was his job to punch back against it. A former wunderkind coach of the Oakland Raiders, he was installed as the American Football League’s commissioner in 1966 while it battled the rival National Football League. But as he girded for a fight, the AFL’s owners struck a deal to merge with their rivals just a couple months into his tenure. It put Davis out of a job — and laid the groundwork for his combative relationship with legendary commissioner Pete Rozelle.

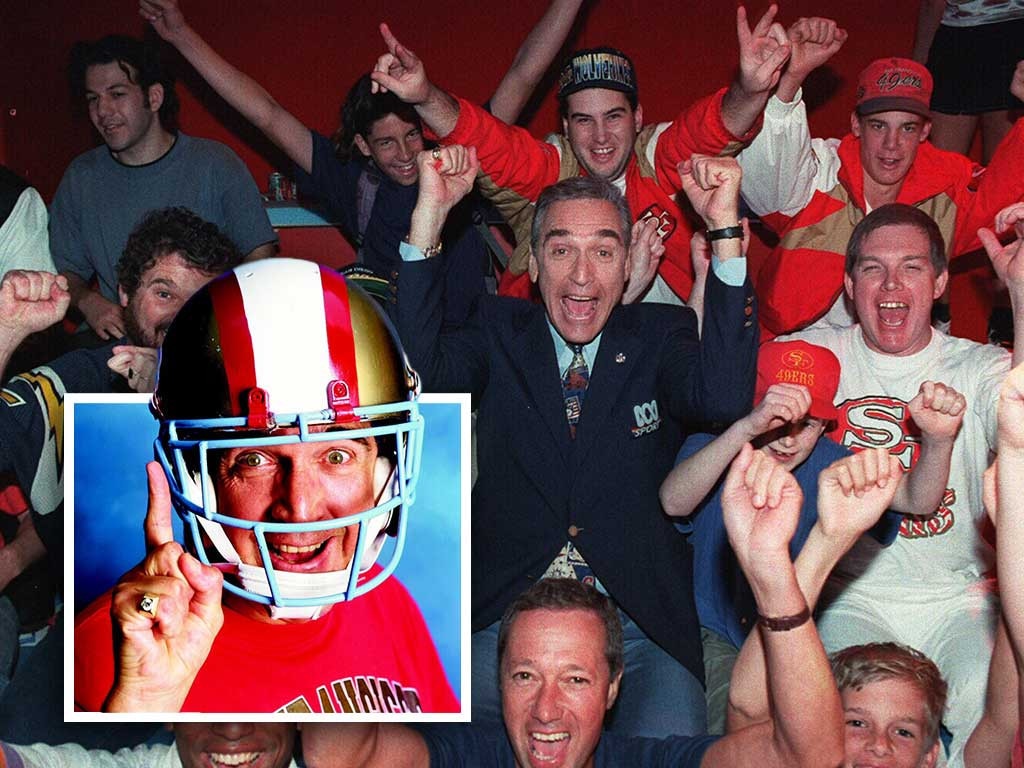

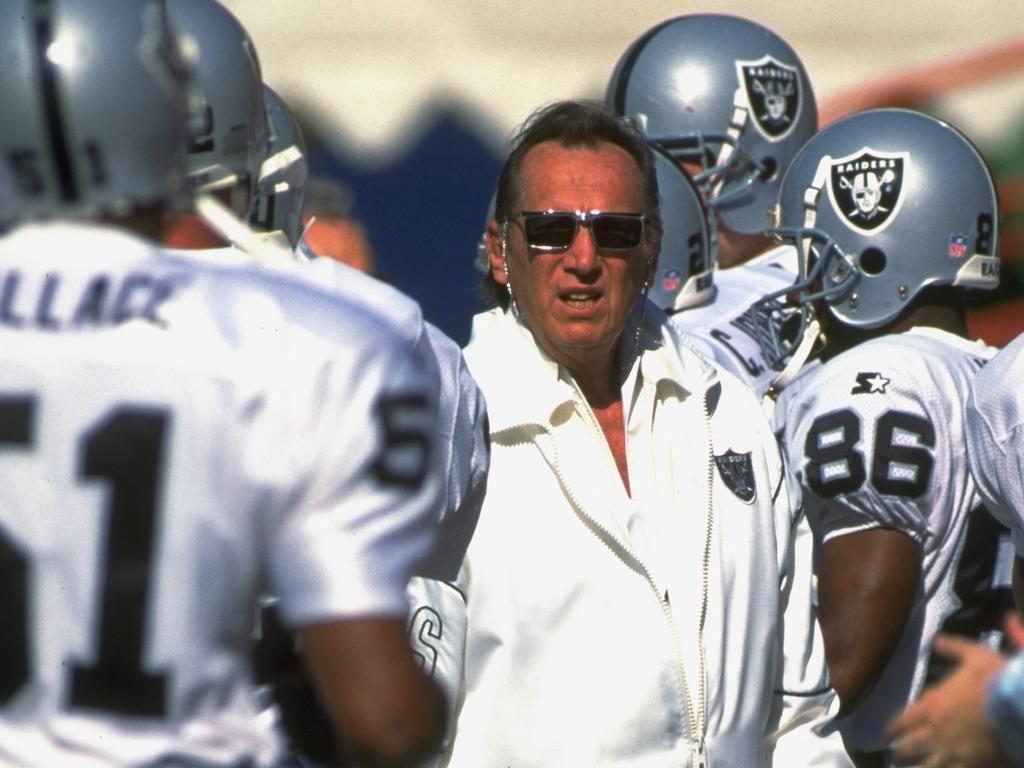

Al Davis returned to the Raiders and soon wrested control of the franchise, but for all the success the team had on the field — it claimed three Super Bowls from 1977 to 1984 and his motto was “Just win, baby!”—he was more famous for something else: being a permanent thorn in the side of the league. And nothing stirred up as much trouble as his efforts to move his franchise.

First, he sued the NFL over a blocked bid to move the Raiders from Oakland to Los Angeles. He ultimately succeeded in 1982 after a court ruled in his favour. Thirteen years later, Davis had a change of heart about Southern California and decided to transplant the team back to Oakland. Once again, the dispute wound up in court, where Davis alleged that the league torpedoed his bid to get a new stadium built in the Los Angeles area. The case bounced through the legal system until it was thrown out in 2007. In all, Davis went to court against the league more than half a dozen times.

But the possibility of moving the team for a third time was never far from the Davis family’s plans. After Al Davis died in 2011, Mark took over with hopes of redrawing the NFL’s map again. A lawsuit wouldn’t be necessary this time. But Mark would have to do something perhaps more difficult: sell the NFL on the idea that Las Vegas could be a viable home for a team.

Davis succeeded in 2017 on the promise of Sin City’s potential to grow as a destination for much more than gambling. And once sports gambling became legal nationwide following a Supreme Court ruling in 2018, any stigma associated with the NFL’s connection to Vegas disappeared.

“The realisation that regulated above-board gambling is not a threat to the integrity of sports … has made a real difference and has allowed the market to open up in Vegas,” said Steve Hill, the president and chief executive of the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority.

In 2020, the Raiders moved into their new home, a $1.9 billion palace called Allegiant Stadium. And just as the league rewarded the Los Angeles Rams for the construction of SoFi Stadium with a Super Bowl in 2022, the NFL promised the Raiders their showcase in 2024.

For the city, it had felt like only a matter of time. There was never any doubt that Vegas could handle an event this size. On any given weekend, city officials say, some 300,000 people flock here to gamble, shop, dine, be entertained, and generally bask in brightly-lit excess. The Super Bowl was expected to push that number to 330,000 — an increase that Vegas has taken in stride.

Plus, the Super Bowl is relatively contained, at least compared with the last global event to roll through Las Vegas. When it hosted a Formula One Grand Prix last November, it happily shut down the entire Strip on a Friday and a Saturday night, immobilising an already traffic-choked city. The road closures related to the Super Bowl could hardly compare in terms of local inconvenience.

In fact, Las Vegas has absorbed the Super Bowl crowd so seamlessly that Chiefs and 49ers jerseys aren’t the only team gear fans have been wearing around town this week. On Tuesday night, the blue and orange of Edmonton Oilers sweaters appeared all over town as the team arrived to face the Vegas Golden Knights. By the next day, most had disappeared and the Super Bowl party proceeded without missing a beat.

But just because the NFL’s relationship with this city has gone so smoothly, it doesn’t mean that the league and Mark Davis have always gotten along in recent years.

Just a couple of years ago, The Wall Street Journal first reported offensive emails sent by coach Jon Gruden, which led to his split with the Raiders in the middle of the season. Those emails had surfaced in connection with the NFL’s investigation into workplace behaviour inside the club now known as the Washington Commanders — and, in a moment that had shades of his father’s rabble rousing, Davis wasn’t afraid to call out the league for how it was handled.

At league meetings shortly after the scandal broke, Davis held court in a hotel lobby and criticised the NFL for not disclosing Gruden’s emails to the team, even though the league had been in possession of them for months. He only found out about the emails, he said, when the Journal contacted the team about them.

Now Gruden is suing the NFL, alleging that the league leaked his emails to harm his reputation. The league has denied any involvement with the leak. As the Super Bowl unfolds here, both sides are anticipating the Nevada Supreme Court to rule soon on the NFL’s request to have the case heard in arbitration.

More Coverage

But Davis has long accepted that some degree of conflict with the league comes with the territory of owning the Raiders.

“Ask the NFL: They’ve got all the answers,” he said of the Gruden situation in 2021. “We really don’t.”

-The Wall Street Journal