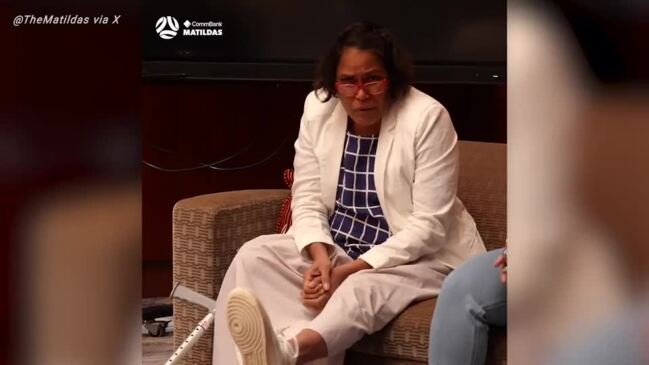

Cathy Freeman: Sydney Olympics, lighting the cauldron and the 49.11 second which changed her life

A day doesn’t go by without someone reminding the face of the Sydney Olympics of the biggest moment of her life. Cathy Freeman looks back on a life-changing 49.11 seconds, 25 years on.

Cathy Freeman still feels like she is riding the wave 25 years on.

A day doesn’t go by where the face of the Sydney Olympic Games isn’t sent back to the biggest moment of her life, to that race, to the stillness and then the noise.

Whether it’s the lady serving the coffee at her local cafe in Melbourne or a parent at her daughter’s school, they all have a connection to the night of September 25, 2000.

They either knew someone who was in the Olympic Stadium or they were lucky enough to be one of the 112,524 spectators there.

Or they remember exactly where they were, and who they were with, as they watched Freeman’s 400m gold medal victory on the TV.

As the star of the show says “it’s taken on a life of its own”.

“After all this time the fact people are still connected to the story, it speaks volumes to the meaning of it, what they take out of it and how it makes them feel,” Freeman says.

“They look at it through either a social lens, the whole reconciliation which comes up a lot and just the unifying power of that moment.

“These are all narratives coming from others, I feel like I am just riding the wave.”

Freeman says there is a bit of “disbelief” about how a quarter-of-a-century has gone by since she fulfilled her childhood dream on the world’s biggest stage.

“I can’t believe it has been 25 years in the first instance, it’s like that conversation where you go, ‘Oh my God I can’t believe Christmas is here already’. There is this air of disbelief about it all.

“It seems like everyone likes to revisit the memories and celebrate it a little bit in their own way. The interest has been overwhelming to be frank, surprising but lovely.”

THE CAULDRON

Her memory of the Games is erratic, different things pop into her mind at different times.

When the Opening Ceremony is raised where she was the final torchbearer, following six legendary Australian female athletes – Betty Cuthbert, Raelene Boyle, Dawn Fraser, Shirley Strickland, Shane Gould and Debbie Flintoff-King – and had the honour of lighting the Olympic cauldron, she goes straight to the infamous malfunction.

“It’s public knowledge now that it broke down for four minutes,” she says about the technical fault which stranded the cauldron as it ascended a mechanical waterfall.

“Looking back it was tricky to navigate through, in the moment I was trying to protect myself and maintain that focus.”

She understood at the time the significance of the ceremony, what it meant in particular for women and Australia’s Indigenous people, and still feels humbled by the enormity of it.

“When Coatesy (John Coates) asked me to do it, you take the man seriously and understand there has been a lot of thought and consideration, multiple conversations and discussions around who was going to fulfil that role,” she says.

“Whilst I was surprised and really humbled, I was incredibly privileged and very honoured to be the one to do it.”

THE RACE

Then there is the race. That 49.11 seconds which changed her life forever. Her tone lowers and becomes more matter-of-fact, this was the serious business back then and it still has her going into that mode today.

First she addresses the Nike hooded Swift Suit which she unveiled for the first time in the final.

“I think it was more my belief in the research and design aspect that Nike presented to me,” she says. “They had such faith in the product and I felt good when I ran in it, which is actually the most important part.

“I wouldn’t have worn it if I didn’t feel comfortable in it … it felt like I was slicing through the air.”

Freeman recalls going into what she describes as a “trance” when she came out of the tunnel underneath the stadium and onto the track. Her appearance set off a tidal wave of noise with the crowd screaming for their hometown girl.

She didn’t hear a thing.

“I remember as I walked out just falling into a trance basically, I just fell into this zone of I’ll just be doing what I know, doing what the coach asked me to do, just do the tactics that would secure a win.

“I kind of felt in control, I didn’t hear anybody before the start of the race, I was just in this different head space. It was all about keeping it simple, keeping it basic, so relaxed but poised and ready.”

THE FINISH

The noise came once she crossed the line and famously sat down on the track, taking her spikes off as the world around her went crazy.

Her life was never the same from that moment.

She did return to the track and won a gold medal for Australia in the 4x400m relay at the 2022 Manchester Commonwealth Games but her heart wasn’t in it and by July the next year she was retired at the age of 30.

Does she regret not making it back to the Olympic stage?

“For what I experienced on the track and being a part of the Opening Ceremony, that was completely mind-blowing, mind-boggling, mind-bending even,

“I guess I look back and I would have liked to have given another event a shot but I think my body was showing signs of wear and tear.

“It all happened the way it was supposed to, it was time for a break. I had been racing and competing since I was five and the expectation on me was always there.

“I got my one childhood dream and that was completely satisfying, that’s it.”

POST-SYDNEY AND DEALING WITH FAME

Dealing with the fame has had its challenges for Freeman, an intensely private person who spent a lot of time running away from the spotlight as she tried to find a rhythm to life away from the track.

“Stepping into retirement, they don’t give you a manual for that,” Freeman laughs. “Being part of a story that takes on its own phenomenon in terms of its impact, no-one gives you a manual for that either.

“Life is always challenging for anybody but then when you have those extra dimensions, it takes a kind of wisdom of trying to strike that point, to get some kind of inner peace.

“At 52 I think I am a bit more calm with it all.

“I was definitely not prepared, there is always this underlying feeling of being underprepared … if you ask my friends I don’t think I’ve changed. That’s all that matters to me, that I haven’t changed.”

BECOMING A MOTHER

One of her greatest achievements has been motherhood to 14-year-old Ruby who she shares with her former husband James Murch.

“It makes life wonderful,” she says about her daughter who likes sports and runs on the track for her school.

“There are days where you are like, ‘I don’t know’, and you’re questioning yourself but it’s OK to not know everything all the time, having others to lean on.

“Questioning yourself isn’t a bad thing, it’s good to stay on your toes, keep yourself in check.

“She definitely has got her own identity, she has her own mind and thoughts. She is amazing to me, and I know any mother would say that.”

Freeman is also kept busy with her foundation, now called Murrup, which works with remote communities to help young children with their learning and school journey. She is also on the Advisory Committee at the Monash University Centre for Consciousness and Contemplative Studies where she gives lectures on mindfulness.

Her latest passion is youth suicide through the Westerman Jilya Institue with indigenous teenager suicide four times higher than non-indigenous.

“It’s really critical work that the Institute is doing and I’m trying to bring a light on it,” she says.

The prospect of the Brisbane Olympic Games in 2032 has her recalling the moment she found out the Sydney Olympics were going to be in 2000.

‘WE BECAME 10-FEET TALL’

“I remember it was seven years beforehand when it was announced and being really excited,” Freeman explains. “I can sort of safely speak on behalf of all Olympians who were aiming for the Sydney Games, we all just became 10-feet tall.

“We all became superhuman for knowing that we had the chance to compete on home soil.

“So all these Australian athletes aspiring for Brisbane, it’s a huge opportunity and a life-defining moment for these young men and women.”

Being Queensland born and bred in Mackay, Freeman isn’t sure what role she will be playing but she knows “emotionally I will get caught up in it”.

More Coverage

“I’m Queensland born, I’ve seen the transformative powers and the uniting powers of the Olympics and I think Australia will do it really well again.”

As for the Sydney Olympics anniversary, Freeman has just been to lunch with her former personal assistant – who sat in the crowd with her family on the big night – and they’ve formulated a plan. A quiet gathering at a local Greek restaurant, the cuisine chosen because Greece is where the Olympics were born.

“It’s perfect, something low-key but meaningful.”