Australian Open 2022: Craig Tiley reveals extreme challenges facing Grand Slam

Craig Tiley and his team somehow pulled off this year’s Australian Open, albeit at crippling cost. Next year’s Open, just weeks away? It’s going to be even harder, he told ADAM PEACOCK.

Craig Tiley and his team at Tennis Australia somehow survived 2021, flying players in like strange interlopers from another planet while Australia sought to protect itself from the rest of the world, a world without vaccines.

So, how is the 2022 Australian Open shaping up by comparison?

“This year is a lot harder compared to last year,” says Tiley in an extensive interview with CODE.

“It’s really hard for a government to commit to a condition.”

The logistics and complexities around getting the tennis world to Australia is a nightmare – 3,300 people from 100 different countries will start arriving in Australia from December 28 – and that’s before taking into account the myriad rules and regulations set by state and federal governments, many of which are prone to change at short notice.

One recent government curveball threatened the whole plan: the emergence of the Omicron variant changed arrival rules into Australia from direct entry to a 72-hour quarantine period.

That rule will be reversed from Tuesday, allowing Tiley to breathe somewhat easier.

“That 72-hour decision would have created a viability issue for us, because you can’t change the charter flights,” Tiley says. “You do that, you lose that charter. Then you couldn’t transport people from different cities around the world.”

Like 2021, Tennis Australia has booked charter flights to transport players who don’t want to risk taking commercial airlines to the event. Seventeen such charters are booked, paid for by TA, who have been subsidising player travel to the Open to the value of $2,500 each long before the pandemic hit.

Every person arriving in Australia will be tested and sent to their accommodation to isolate until a negative result is returned.

Vaccination, too, has thrown up some variables. The simplest way for players to enter the country is to be jabbed, however there is a straight exemption given to those who have tested positive to COVID-19 in the last six months, as ATAGI acknowledge the immunity built from a recent positive case.

Also, those who are not vaccinated can apply for a medical exemption from ATAGI.

Tennis Australia is distancing itself from deciding on which unvaccinated players, if any, are allowed into the country to play at the Australian Open.

“There’s a medical panel set up, and it goes to that panel,” Tiley says. “They are in the process of making those decisions the weekend just gone. Then the panel will advise them [the unvaccinated] on the success of that exemption.

“It’s a high bar to get a medical exemption. The easiest way is to get vaccinated.”

It remains a mystery if Novak Djokovic will travel to Australia this summer.

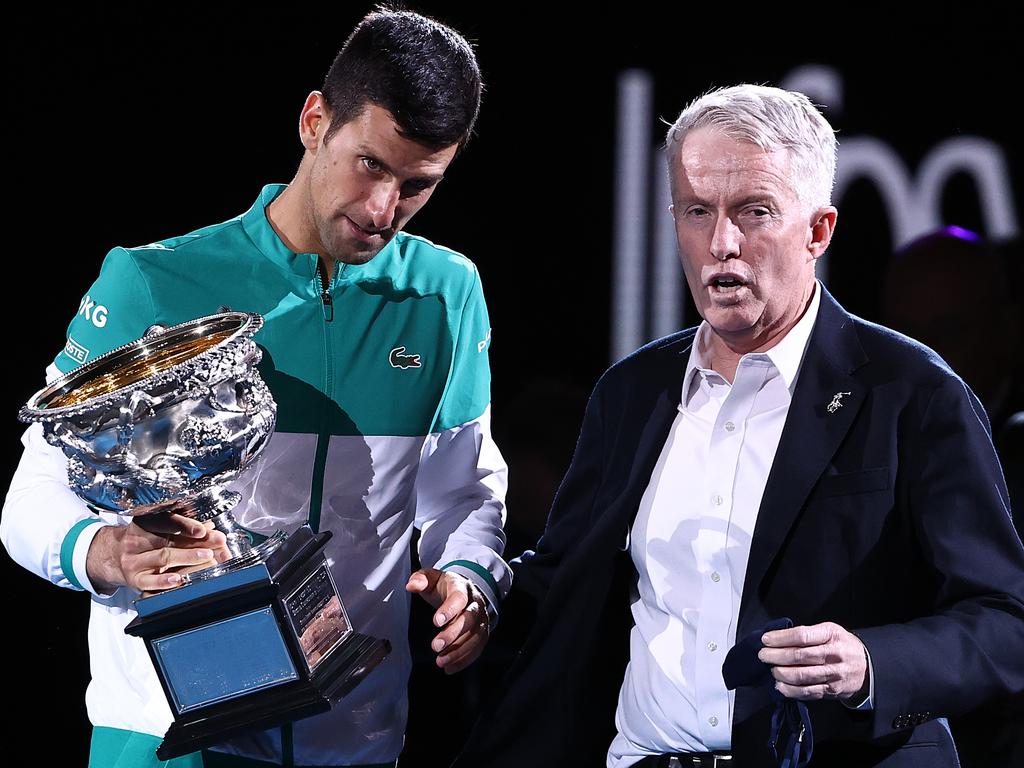

ATAGI has promised complete anonymity for those applying for a medical exemption. Tiley doesn’t know if Djokovic will make the trip for a tenth Australian Open title quest next month, although he does have some sympathy for the world No. 1.

“In many ways it’s been a bit unfair on Novak,” Tiley says. “He’s said his medical information is private and confidential.

“He’s won [the Australian Open] nine times, which is really remarkable. Of his 20 grand slam titles, nearly half [were] here. Because of that journey [I have] spent a lot of time with him … I completely understand where he’s coming from, relative to his medical position is a personal one and he’s got every right to keep that personal. He’ll disclose, shortly, that position.”

While exact figures are impossible to obtain, there is a view on the tour that vaccine uptake has accelerated to the point that an overwhelming majority of players are now jabbed.

And while the worldwide attention that would come with Djokovic breaking the men’s all-time grand slam record would help the Australian Open, Tiley is adamant one man won’t make or break the event, and has deployed a small army to deal with the many issues confronting the tournament.

Postal delays have resulted in a delay of Hawkeye equipment. Even procuring tennis balls has proven a complex and expensive matter, with freight costs blowing out in order to ensure they are delivered in time.

Tiley knows more issues will arise before the tournament starts.

He just doesn’t know exactly what they are yet, other than the certainty that all will impact the bottom line.

The 2020 Australian Open, held as the initial stages of the pandemic played out in Wuhan, was the biggest ever with revenue topping more than $400 million – an incredible figure given that, just 20 years ago, it was in the region of $20 million.

The enormous costs associated with staging the 2021 Australian Open in a biosecure environment saw Tennis Australia burn through their $80 million in cash reserves and take out an additional $40 million loan.

“People said you shouldn’t have had the event but it would have been a lot more costly to not have the event,” Tiley says.

Revenue from sponsorship and television rights – two massive contributors to the financial health of tennis across the country – would have dried up in the event of a cancellation.

Running the event at a substantial loss at least allowed for business continuity.

“We continued to fund our members associations at a lower level … kept them whole,” Tiley says. “Thirty seven per cent more adults, 28 per cent more kids playing: [the] outcome is we’ve got a fast growing sport, [the] challenge we have in the next 18 months to three years is to capitalise on that, and retain it.”

Central to those plans is the revenue from the Australian Open, which won’t return to 2020 levels for the foreseeable future but, barring any significant U-turns from the state government, could benefit from uncapped crowds this time around.

Tiley insists there will be no need for the on-site separation of fans into zones, as was the case in 2021, despite relatively high infection rates in the community and the uncertainty associated with the Omicron variant.

Tiley hasn’t noticed any substantial softening of ticket sales on account of Omicron, and notes the corporate hospitality sales remain strong.

There will be no mandate for fans to wear face masks if there is no mandate from the government – and Melbourne Park is a government-run site – although patrons will be free to wear one.

“It is going to be safe,” Tiley says. “You will have to be vaccinated to attend.

“The plan now is pretty straight forward. The issue is the variables. Will there be more lockdowns? We doubt it. Would there be borders closed? Doubt it. International flight [restrictions? Doubt it.

“Even though predictions are [that] the numbers will keep climbing – obviously conditional on Omicron – but the commitment the government has made so far is they are treating Omicron as it’s not changing what they are doing.

“They are in a position that they want to get on with life and get on with managing it. That’s been communicated to us.”

TA is hopeful the 2022 Australian Open will not be subject to the same levels of chaos as last summer, which included a mid-event lockdown that resulted in some of the tournament’s biggest matches played in empty arenas.

There are lead up events in Sydney and Adelaide to negotiate first, but Tiley is confident the NSW and South Australian governments are on the same page in regard to the logistics required.

TA, for instance, has been assured by the South Australian government there will be no repeat of the Pat Cummins situation, whereby the Australian men’s Test captain was forced into seven days isolation after being deemed a close contact while dining indoors. Those rules are set to adjust once South Australia hits the 90% double vaccination mark just after Christmas and before Adelaide‘s lead-in events.

As for the Victorian government, Tiley senses a desire to use the tournament for a grander purpose.

“Victoria are particularly keen for us to have an event … and to show the world we’re back in business and [again] get over a billion people around the world-watching,” he says.

Tiley continues: “It’s been physically and mentally exhausting. No one has had a break since 2019. It has been very difficult, [I am] so proud of our team, [it is] remarkable what they achieved in 2021, and what they will achieve in 2022. [It] hasn’t been straightforward.

“But having an opportunity to put on an event for Melbourne … we hope we can provide some leadership toward getting back to a Covid-normal world and, if we can achieve that, it would be something special.”