Australian Open 2022: James Duckworth’s journey back from No.1072 to top 50

James Duckworth has fought chickens for court space in Turkey, feared he was being abducted in Brazil and gone under the knife eight times in six years. He’s finally cracked the top 50, and not done yet.

The first time James Duckworth faced Roger Federer was in the opening round of the 2014 Australian Open, where sweaty fans at Rod Laver Arena made regular quacking noises, and, bizarrely, one even tooted a whistle imitating the distinctive sound. The man known as “Ducks” lost 6-4 6-4 6-2 but gained an enduring memory – one still shared by the Swiss champion regarded by many as the GOAT.

“Every time I see (Federer) or I walk past him, he starts quacking, or he calls me ‘Quack’ as well, so it’s pretty funny,’’ Duckworth says. “I just say, ‘Hey Rog’. I don’t really have a sound or something for him. It’s just Rog.’’

Back then, almost eight eventful years ago, Duckworth was a former top 10 junior working his way towards the top 100, where he would peak in part one of his career at No.82 in 2015. Yet, ominously, the YouTube highlights from that AO first round already show strapping on the 21-year-old’s right elbow.

There would be more. In multiple places. Much more.

At that stage, in contrast, No.6 seed Federer was the 32-year-old owner of 17 major singles titles and a then-record 302 weeks at No.1; on that sweltering Melbourne afternoon he would move past Wayne Ferreira to set a new record for the most consecutive appearances – 57 – at grand slams.

Now it is Federer’s ageing body that is failing him, as he continues a long stint on the sidelines that will stretch beyond the AO well into 2022, if he ever returns at all. Meanwhile, Duckworth has enjoyed a healthy, career-best season that ended in the top 50.

At last.

The Australian No.2 can potentially claim some form of No.1 status, though: for the number of operations endured by active players. From shoulder to elbow to foot, he suspects the eight since 2016 leave him atop the surgery leaderboard. “I reckon I’ve probably won that, yeah,’’ says Duckworth (further investigation reveals him to be equal with the unfortunate Juan Martin del Potro, who last played in mid-2019).

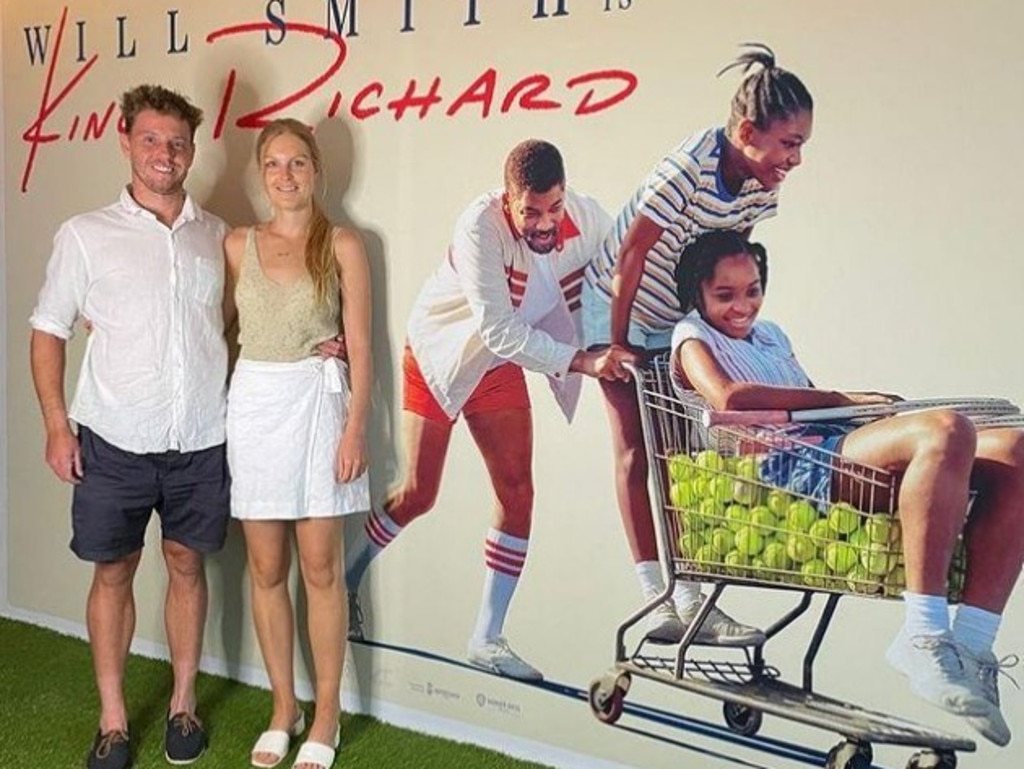

Indeed, the son of an orthopaedic surgeon specialising in, yes, shoulders and elbows, has just bought his first home in Brisbane with partner Madison Bowles, a soon-to-be surgical registrar – meaning Duckworth is intimately acquainted with a medical world that, in some respects, he would prefer to know far less about.

The upside has been some discounts from his dad’s doctor mates, and the fact he has now been anaesthetic-free since a shoulder debridement (removal of dead tissue causing persistent pain) in early 2020. A recovery window forced open by the Covid-19 shutdown then saw Duckworth genuinely resting up on the recommendation of Pat Rafter, who‘d undergone the same procedure many years before, to immense benefit.

The 2021 highlights: two top 15 scalps (David Goffin in Miami, Jannik Sinner in Toronto), a debut third round at a major (Wimbledon), and quarter-final at a Masters 1000 (Paris), a maiden ATP Tour final (Kazakhstan’s Astana Open), a treasured first Olympic appearance in Tokyo (for a second round loss) and over $1 million in prizemoney (which, considering expenses, doesn’t stretch as far as you might think).

Tennis Australia’s head of professional tennis, Wally Masur, says more players are now breaking through in their late 20s, even early 30s. “Could Ducks have got here a bit earlier without all those injuries? Yeah, possibly. But that’s the game, isn’t it? Players do have to deal with these setbacks.

“Johnny Millman’s had a few. Roger’s a bit of an anomaly, isn’t he? (Federer) kind of floated through his career for so long uninjured, and he’s kind of playing a price at the back end. Rafa (Nadal) of course has been patched together a few times. And Andy Murray. What’s he got? A metal hip? So it’s sort of the nature of the game.’’

Young Ducks

Masur first saw Duckworth training at Sydney’s Homebush Academy just as he entered high school, noting both the extreme forehand grip, and a commitment to improving a serve that is now world-class even as a 12-year-old.

“What worried me was he had a couple of stress fractures as a kid – it started off in his back, from memory,’’ Masur says. “I remember talking to his dad, who’s a surgeon, and you don’t like to go to the father of a promising kid and say, ‘Oh, look, by the way, we’ve managed to give your kid a stress fracture!’’’

Dr David Duckworth said such issues were not uncommon in teenagers, while often remaining as mere soreness or stiffness among the less active. “So he was really good about it and James was really good about rehabbing,” Masur says. “He never got despondent, he’d have these setbacks but he’d do all the right things to get himself back on court.’’

That attitude has endured, even through the challenging times. “In 2015, I’d just turned 23 and I’d got to (number) 80 in the world, but then things came crashing down pretty quick, and it was a really tough path for a couple of years,’’ Duckworth says. “There’s a lot of doubt that creeps in. Whether you can get back to a certain level; whether your body can get back to the rigours and grind of the tour.’’

The low point was at the end of 2017, as Duckworth tried to prepare for the Aussie summer after two major foot operations and a pair of more minor shoulder procedures.

“I couldn’t run and I couldn’t hop and I couldn’t jump pain-free. I was just questioning, ‘If I can’t do these things, how am I ever gonna play again?’ My surgeons weren’t sure if any other operations would help, and we tried a few injections, we tried a few different things with orthotics and it was looking pretty grim with how we were gonna get rid of this pain and get me back to doing all those things that I needed to do to be a tennis player.’’

As to what else he might be? “Look, it probably never really got to that stage. I always held out belief.’’ There was a true love of the game, too, which remains. Even when he’s not playing, he’s watching, thinking, preparing. Coach Wayne Arthurs is something of a kindred spirit, and integral to Duckworth’s recent success.

“I feel like I would have been so disappointed or had a feeling of underachievement if I finished my career only sort of getting to 80 in the world,’’ says the current No.49. “I thought that I could play to a better level than that and I would have always been wondering, ‘What if?’’’

Masur adds some insight into the reasons for Duckworth’s second coming, apart from the obvious one: that his body has now permitted it. First, a slightly unorthodox, unpredictable style that involves an element of surprise brings what the former Davis Cup coach describes as the need to master many plays.

A lot of established players, he says, “do about two or three things really, really well, and that’s about it, but they kind of perfect the art. Whereas James can do a lot of things. He’s capable of playing at the net. He’d stay back, he’d use a slice, even forehand slice, drop shots, come in spontaneously by taking a couple of second serves on the rise.

“So I think it’s kind of just mastering all of the shots and getting his house in order in terms of the game plan. I think he’s done a good job of that this year. Really judicious in his shot selection. And working with Wayne Arthurs, a really dedicated one-on-one coach, I think is important.’’

So, too, something Masur noticed on a chalkboard at a Sydney gym recently, which resonated more than the usual twee motivational slogans. The three things you need to do to improve: 1. show up, 2. show up, 3. show up.

“That’s what James has done, and that is so key. He and Johnny Millman are similar in that they both just show up and do the right thing every day. Do all the little things to be better and to rehab absolutely correctly and that’s the result: you make the most of your potential.’’

The lean years

Duckworth and his close friend, Brisbane training partner and Olympic roommate Millman also boast some, well, memorable experiences from the tennis backwaters and off-off-off Broadway venues that are the antithesis of the more glamorous and lucrative world inhabited by the sport’s marquee names.

For Duckworth – in 2018, when ranked No.1072 in the early stages of his latest comeback – that included heading from five-star treatment at Roland Garros, where his main draw entry had come via a protected ranking, to a lowly Futures event in Antalya, Turkey.

No spectators, line judges, ball kids, or new practice balls. Sometimes no water from the hotel taps. Certainly no variety at lunch. But plenty of wild chooks and roosters roaming around the court.

Which was not as bizarre as his terrifying late night travel ordeal in South America in 2014. Heading to a tournament in Rio Quente, Brazil, a taxi ride from the airport sabotaged by flat tyres turned into a bizarre truck ride and then a car trip with strangers, all the while fearing he was being abducted.

“At the time I was scared. I was like, ‘Geez, I’m in the middle of Brazil, no one knows exactly where I am. Hopefully something doesn’t happen to me here’ … But post it happening and getting to the hotel, all fine, yeah, it’s just a good story.’’

In 2021, there has been an even better one, despite a gruelling but successful second stint on the road after a single trip home to recharge in April-May. The fact that progression is rarely linear, though, was borne out by the fact that his upset of Sinner – where extra motivation came via the commentators previewing prematurely the Italian’s prime time clash with Daniil Medvedev – was soon followed by brutal losses in Winston-Salem and at the US Open, where Duckworth failed to convert nine match points.

Up. Down. Up again. After a reassuring pep talk from Arthurs, Duckworth won 14 of his next 16 matches.

Tournament life itself was a constant, and stressful, juggling act. As Covid protocols and restrictions eased during the year, there remained the constant worry of contracting the virus, and thus being unable to play while the expenses mounted (a return flight for Arthurs for his most recent trip was a relative bargain at $10,000) and prize money cheques were potentially foregone.

On the court, Duckworth – nominated for the ATP’s Most Improved Player Award in 2021 – says his rise is down to playing with more aggression in the big moments and being more comfortable doing so, rather than any sweeping changes in his game.

“A move of 50 or 60 spots from inside the top 100 is significant,’’ Masur says. “It requires a lot of wins and a lot of points, and you’re playing the best players in the world to do it.’’

Profile? What profile?

Duckworth and friends used to be trivia night regulars at Brisbane’s Norman Park Bowls Club. In 2016, I asked Millman, who was one of them, how many in the room could correctly nominate him as the answer if the question was to name Australia’s third-ranked tennis player behind Nick Kyrgios and Bernard Tomic.

“Ah, maybe my sisters would know, ‘Ducks’ would probably know, and that’s about it,” laughed world No.66 Millman, completely unbothered.

So, to Duckworth: how many at the trivia night could identify the current Aussie No.2? “Yeah, probably Johnny’s sisters. And him. That’s about it, I’d say.’’ Also unfussed.

Controversially, it was not enough to earn selection in the original Australian squad for the Davis Cup finals. Team nominations were required well in advance, and Duckworth’s own hot run of form came after captain Hewitt’s preference for Millman, Alexei Popyrin and Jordan Thompson alongside de Minaur and doubles specialist John Peers.

By the time Thompson was forced to withdraw due to Covid-19 and Duckworth approached to be his replacement, he was committed to returning home and completing his third stint in quarantine, exhausted after a demanding season and keen to reunite with partner Madison after six straight months on the road.

“I was pretty cooked by the end of it. Physically, mentally, I was due for a break,’’ he said from quarantine in Adelaide, his third fortnight of isolation for the year. “I want to see my girlfriend, I want to spend a night in my house. I need a training block, I needed a couple of weeks off, I just wanted to be back in Brisbane, so I was pretty ready for it to end.’’

More broadly, Duckworth has spent so much time among the support cast that it’s interesting to consider where he fits into the narrative of Australian men’s tennis, with Masur citing the attention-grabbing deeds of a young Tomic and then Kyrgios, both top 20 residents at their peak.

“The game is always driven by a few personalities and those two had an amazing ability to take all the oxygen out of a room,’’ Masur says. “They really drove a lot of stories and interest in the media and with the public. So James was probably a victim of that.

“No disrespect to James, because I’ve been in that place: the guy ranked 47. It’s solid and it’s pretty commendable in an international sport. But when you get players like Kyrgios or Tomic who have top 10 potential and Thanasi (Kokkinakis) the youngster before he suffered some injuries, and we had Sam (Stosur) winning Slams and Ash (Barty) emerging, that’s what drives the game.

“So I always maintain that for guys like James, the more money and the more profile those people have, the better you’ll do, because the sport’s going to be in a better position. But I think he’s poised now and he’s very capable of getting himself inside that top 32 to be seeded in a slam, and I think he’s got the serve and the game now to do some damage and let’s hope it’s at the Aussie (Open).’’

Where he needs to be

Look no further than the ‘best player ever’ debate involving the three men tied on 20 major titles, or the endless fascination around Serena Williams’ seemingly doomed quest to equal Margaret Court’s all-time singles record of 24, for a reminder that the slams are largely where reputations are forged.

They are also where Duckworth went five years between match wins after the 2016 Australian Open – although, admittedly, a string of first-round draws against high seeds added to the degree of difficulty.

This could be his time, for never has the strong, big-bodied all-rounder been better positioned for a strong home summer. Confident and experienced, his main draw entry at Melbourne Park is assured. He is healthy, will be fresh after a pre-Christmas training block with Arthurs, and relish a national team return in the ATP Cup.

He is, in short, where he has always wanted to be.

Well, almost, given that the sense of achievement that came with the top 50 entry that had been his goal for six months – but in truth, far longer – was surprisingly brief.

“I spoke to my girlfriend the day after I did it,” Duckworth says. “I’d got there. Great. And then the next day, ‘Ooh, I wanna be top 30!’ So I guess you’re never really satisfied. It was only about a day when I was happy … And then I was like, ‘Right, I want to get seeded at a grand slam, I want to be top 30 now’.’’

Since 2018 he has taken nothing for granted, able to view each small milestone through the lens of what it has taken to tick them off, including “so much mind-numbing rehab and physio”.

“You do realise it’s all worth it in the end, if you can get through it, to be at the best events in the world.’’

Masur too sees a player whose best ranking if ahead is he can stay healthy; one who knows his body, and how to manage his training, workload and schedule.

To, dare we say it - and we will because Roger Federer can’t have all the fun with the quack-related gags - get all his ducks in a row.